- Pages: 384 p.

- Size:220 x 280 mm

- Illustrations:263 col.

- Language(s):English

- Publication Year:2025

- € 75,00 EXCL. VAT RETAIL PRICE

- ISBN: 978-1-915487-51-3

- Hardback

- Available

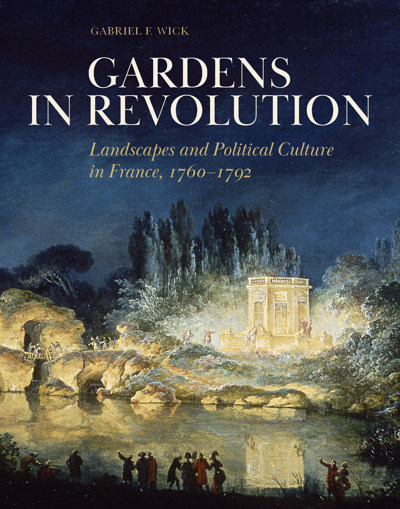

Gardens in Revolution offers an incisive look into how aristocratic and royal landscapes were used to represent dissent, undermine, and then ultimately recast and reinvent absolutism in the pivotal decades preceding the French Revolution.

Gabriel Wick is a Paris-based landscape historian. He teaches art history at the Paris campus of New York University, and also lectures for the École du Louvre. He received his doctorate in history from the University of London – Queen Mary in 2017 and holds a masters in landscape architecture from the University of California, Berkeley, and a masters in historic landscape conservation from the École nationale supérieure d’architecture – Versailles.

France in the mid-1760s witnessed what the aphorist and garden lover the prince de Ligne hailed as “La révolution du goût” – the revolution of taste. A small number of dissident and philosophically minded aristocrats remade their gardens in the bizarre and eccentric manner of the English. The informality and apparent naturalism of these jardins anglais stood in marked contrast to the symmetry, regularity, and proudly assumed artifice of the jardins à la française, the century-old legacy of André Le Nôtre and his master Louis XIV. The English-inflected aesthetic was all the more controversial because France had just suffered humiliating defeat at the hands of England in the Seven Years’ War. Landscape gardens formed part of a broader taste for English fashions, pastimes, and mindsets that was derisively termed Anglomania by traditionalists. Louis XVI opined to his brother-in-law Joseph II that anglomanie was the most pernicious threat to the well-being of France.

What did it mean for the kingdom’s great dynasts to reframe their identities in the image of the nation’s rival? Were these aesthetic developments simply a question of fashion or did they portend a deeper instability and discontentment in the upper echelons of the Bourbon monarchy? How did new English-inflected settings allow aristocrats and the people to interact differently?

Gardens in Revolution argues that royal, aristocratic and public gardens were catalysts in early modern political culture: settings that allowed dynasts to redefine their identities, transform their interactions with the press and the people, and in so doing contest the limited influence and autonomy afforded them within the Bourbon state. Covering the three decades from the end of the Seven Years’ War to the abolition of the monarchy, it charts how estates and gardens like Marie-Antoinette’s Petit-Trianon and Saint-Cloud, the comte d’Artois’ Bagatelle, or the duc d’Orléans’ Monceau and Le Raincy served as instruments of communication, self-expression and self-representation. It argues that English-inflected aesthetics were a critical means for grandees to manifest their “affabiliteì,” or openness to the public, and their dissatisfaction with the current political order.

Introduction

Chapter 1: In the Gardens of the Princes Patriotes: The princes de Conti and Condé and the Duc d’Orléans

Chapter 2: Triumph through Disgrace: The Duc de Choiseul at Chanteloup

Chapter 3: Révolte à l’Anglaise: The Duc de Chartres at Monceau and Saint-Leu

Chapter 4: A Revolution at Court: Marie-Antoinette, the Petit-Trianon and the Reinvention of the Royal Garden

Chapter 5: Prince of the Public Sphere: The Comte d’Artois’s Landscapes

Chapter 6: The Crown’s New Estates: Rambouillet and Saint-Cloud

Chapter 7: A Modern Domain for a Republican Prince: Orléans and Le Raincy

Conclusion: The King’s Last Garden: Tuileries

Bibliography