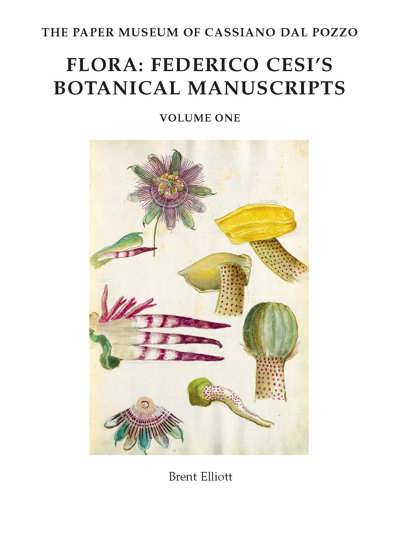

Flora: Federico Cesi's Botanical Manuscripts

Brent Elliott, Luigi Guerrini, David Pegler

- Pages:3 vols, 1328 p.

- Size:220 x 285 mm

- Illustrations:869 col.

- Language(s):English

- Publication Year:2015

- € 230,00 EXCL. VAT RETAIL PRICE

- € 140,00 EXCL. VAT DISCOUNT PRICE VALID UNTIL 30 Jun 2026

- ISBN: 978-1-905375-78-3

- Hardback

- Available

"The lasting value of these drawings remains their pioneering use of the microscope. Cesi’s artists, in the 1620s, recorded details of plant anatomy with a precision, and on a scale, that would not be matched for centuries. Engravings were made of a few of the drawings; if the entire series had been published at the time, how the science of botany would have been advanced." (Brent Elliott, in: The Financial Times, 29 May 2015)

“These three volumes are the latest entries in the series of publications that make up “The Paper Museum of Cassiano dal Pozzo.” (…) As with earlier volumes in the series, these combine outstanding scholarship with beautifully reproduced illustrations.” (Janice Neri, in Isis, 107/4, 2016, p. 836)

“It is a credit to the series editors, scholars, curators and publishers that high standards of scholarship have been sustained throughout the series, including this set (…) it is only with the publication of this goldmine that scholars are in a position to ask well-founded questions with rich returns.” (Sachiko Kusukawa, in Archives of Natural History, 45/1, 2018, p. 181-182)

Brent Elliott was the Librarian of the Royal Horticultural Society from 1982 to 2007, and is now the Society’s Historian. He is the author of Victorian Gardens (1986), Treasures of the Royal Horticultural Society (1994), The Country House Garden (1995), Flora (2001) and The Royal Horticultural Society: A History 1804–2004 (2004). A former editor of Garden History, he is now the editor of Occasional Papers from the RHS Lindley Library; among his contributions to this series are ‘Charles Darwin in the British horticultural press’ (2010) and ‘Eighteenth-century science in the garden’ (2011).

Luigi Guerrini is a historian specialising in the history of science in Italy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and particularly in the history of the early Accademia dei Lincei (1603–30). He has held post-doctoral fellowships and research positions in Italy and abroad. He is the editor of the twovolume edition of Federico Cesi’s Apiarium (2005–6), the author of I trattati naturalistici di Federico Cesi (2006) and a contributor to Part B.VIII of the Paper Museum, Flora: The Aztec Herbal (2009).

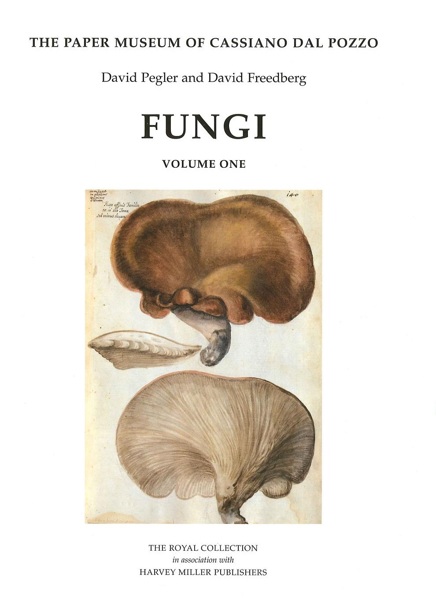

David Pegler is the former Head of Mycology at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and co-author of Part B.II: Fungi (2005) in the Paper Museum series. His taxonomic research has specialised in tropical and temperate Basidiomycetes, for which he received a Science Research Council individual merit promotion, and he has published 16 books and more than 300 scientific papers. He is a Fellow of the Linnean Society, London, of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, and Centenary Fellow of the British Mycological Society. He has held visiting professorships at the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, Łódz´, Poland, the Instituto de Botânica, São Paulo, Brazil, and the University of Jilin, China.

This three-volume catalogue presents five manuscripts containing some 780 mainly botanical drawings, now in the library of the Institut de France. They were produced for Federico Cesi in the 1620s to further the researches of the scientific society he had founded in Rome, the Accademia dei Lincei, of which Cassiano dal Pozzo was a member. The manuscripts were acquired by Cassiano in 1633 following Cesi’s death, together with three companion manuscripts dedicated to drawings of fungi (published in Part B.II of the catalogue raisonné). Many of the drawings depict plants such as ferns, bryophytes, mosses and liverworts, which had been considered ‘imperfect’ because (like fungi) they seemed to lack reproductive structures – flowers, fruit or seeds. In 1624 Galileo gave his fellow academicians a microscope, and with this novel ‘aid to the eyes’, wrote another Linceo, ‘our Prince Cesi saw to it that many plants hitherto believed by botanists to be lacking in seeds were drawn on paper’. Indeed, these drawings constitute some of the earliest microscopic studies in the history of science. One manuscript is dedicated to illustrations of seaweeds and is the first known sustained study of this subject, while another is a miscellaneous volume that includes 30 prints as well as drawings of fungi and lichen, insects, a bat, a hermaphrodite rat and other curiosities. Introductory essays discuss the importance of these drawings to Cesi’s researches and how the manuscripts made their way into the collections of the Institut de France, their botanical content and place in the history of botanical illustration. All drawings are reproduced as full-plate colour illustrations and accompanied by botanical identifications and commentary.