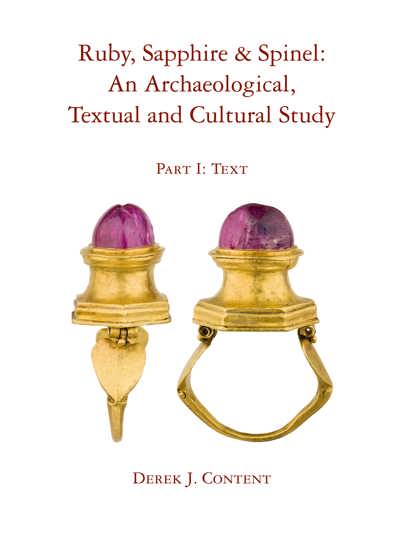

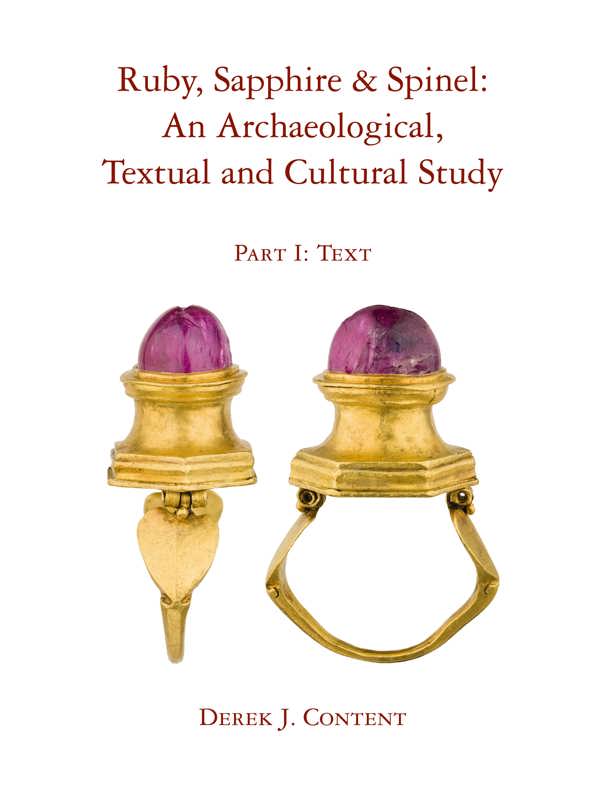

Ruby, Sapphire & Spinel: an Archaeological, Textual and Cultural Study

Derek J. Content

- Pages:2 vols, 452 p.

- Size:225 x 300 mm

- Illustrations:2 b/w, 320 col.

- Language(s):English

- Publication Year:2016

- € 180,00 EXCL. VAT RETAIL PRICE

- ISBN: 978-2-503-56808-9

- Hardback

- Available

“This is an extremely important book on the history of gems and jewellery (…) Not only would I highly recommend this book to gemmologists, but would suggest it is a must-buy for appraisers and jewellery historians.” (Richard W. Hughes, The Gemmological Association of Great Britain)

“Antiquarians and students interested in the history of glyptic, particularly gem engraving in western cultures, and archaeologists specialized in the ancient gem trade, will find that Part I of this two-volume set provides illuminating discussion with much useful information not found anywhere else. (…) Together, the two complementary volumes are an indispensable reference in any library.” (Lisbet Thoresen, in The Pegmatite, April 2017, p. 22)

Until about two hundred years ago, no gemological distinction was made between ruby and spinel. Red spinel and red ruby are not infrequently found together and though gem cutters and engravers noticed and commented on the difference in hardness, the assumption was that spinel was simply an “unripe” version of ruby. Additionally, ruby and sapphire are both versions of the mineral corundum, distinguished only by color and minute traces of the metal oxides that caused these different colors. Sapphires may be pink, yellow, and green as well as blue, while rubies come in many shades of red which, inevitably causes confusion as one person’s pale red ruby is another’s pink sapphire – there are no absolutes. Consequently, the nomenclature is confused, both within early texts, and also in later translations of those texts. The ancient authors could only report on the basis of the information available to them at the time, while those writing the later translations were fine textual scholars or epigraphers, but not infrequently poor gemologists, not familiar with the mineralogical distinctions between the gems. It has often been difficult to get an overarching view of the many different factors that all played a part in the spread of precious gems and of the dissemination of knowledge about them. Given the paucity of available information concentrating exclusively on the use of ancient precious gemstones, the author combed the literature for relevant references. A surprising amount of descriptive and factual information was found, mostly scattered throughout early texts. The most interesting passages were selected and wherever possible the original authors’ words were quoted rather than paraphrased. The early translations in the languages used by 17th–19th century scholars are given, names of people, places or objects that otherwise might have remained obscure are explained. Gems travel. They follow wealth and because of their natural immutability, the only way they can be identified by culture is by the way man has affected their appearance, deliberately or accidentally. The dating of gems that are still in original period settings is easier because the dated typology of rings and jewelry settings generally, is more secure than the study of gem shapes, while the study and dating of specific faceting styles of unmounted stones is still in its infancy.