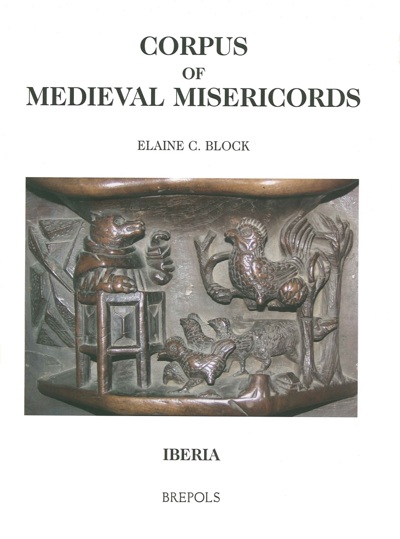

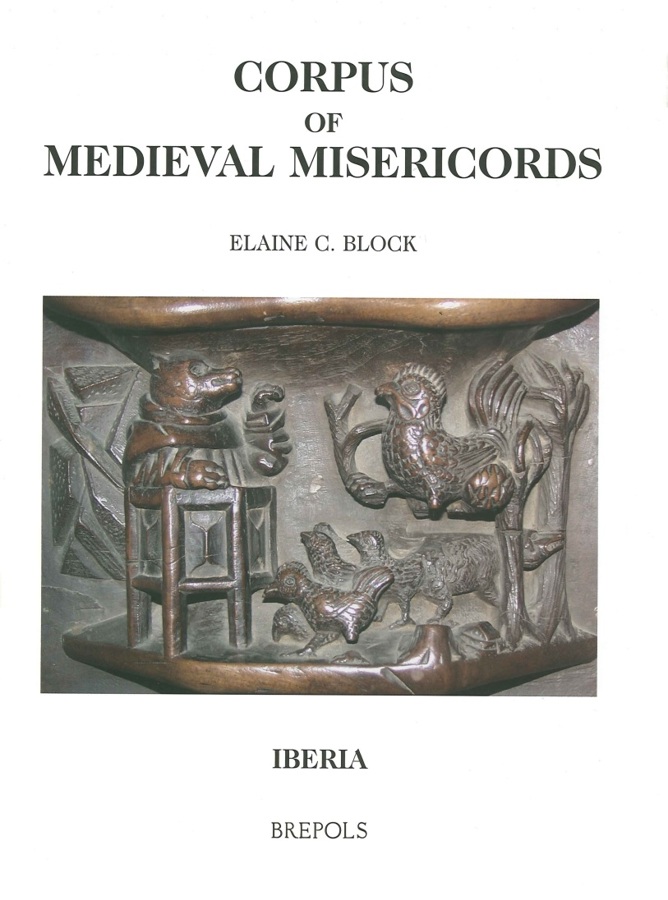

Corpus of Medieval Misericords. Iberia

Elaine C. Block

- Pages: 284 p.

- Size:215 x 280 mm

- Language(s):English

- Publication Year:2005

- € 135,00 EXCL. VAT RETAIL PRICE

- ISBN: 978-2-503-51499-4

- Hardback

- Available

"Blocks Corpus ist ebenso relevant für die Theologiegeschichte, die Volkskunde oder die Motivforschung in der Buchmalerei wie für die Kunstgeschichte mittelalterlicher Skulptur." (S. Wartena in Sehepunkte, 5 (2005), nr. 12, 15.12.2005)

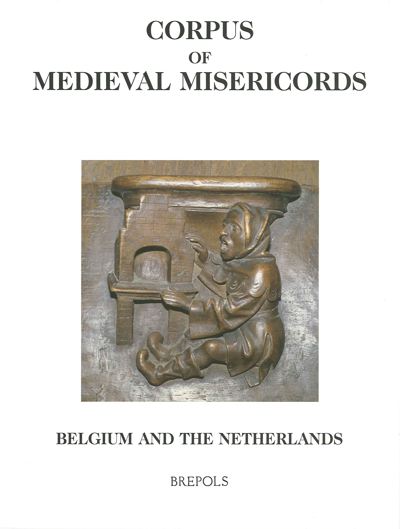

The Corpus of Medieval Misericords (XIII-XXVI) consists of five volumes; the first four focus on the misericords and related choir stall carvings in specific regions of Europe. The fifth includes an extensive iconographic index of themes common to various countries as well as themes that are unique to a single country.

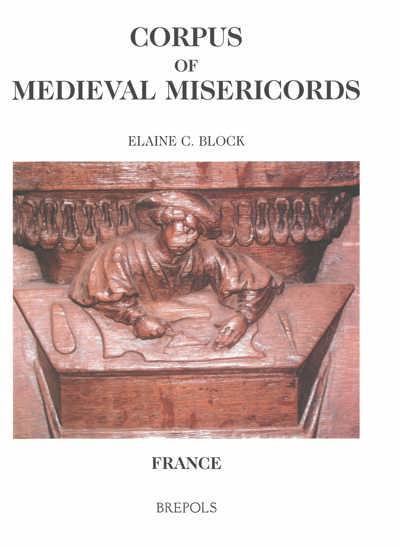

Volume I of this series, Medieval Misericords in France, covers approximately 300 churches that still contain gothic misericords with carved figures and narratives inspired by oral traditions suh as proverbs and folk tales, as well as by manuscript marginalia, romanesque capitals, illustrated bibles, engravings, playing cards... A vast portrayal of medieval life - rural activities, urban occupations, conjugal relationships, monastic life -- is displayed in these carvings under the seats of choir stalls along with costumes of the times, town and collegiate architecture, mechanical devices. Puns and rebuses are often intertwined with these themes to produce comic and, to twenty-first century eyes, mysterious puzzles. The global view of misericord carvings, generally ignored in studies of medieval art, is here presented as a multidisciplinary basis for further research by sociologists, historians, archeologists and other medieval scholars.

Following volumes include misericords in Iberia, Flemish and borthen Europe, Great Britain.

This volume examines the medieval choir stalls, especially their misericords, in the Iberian Peninsula: Portugal and Spain, most of which are extraordinarily beautiful. Fourteen churches in Spain and two in Portugal still have sets of Gothic choir stalls. These sixteen cathedrals, churches and monasteries compare with over two hundred churches with medieval choir stalls in France. The Iberian choir stalls are mainly the original sets for that church. Those at Belmonte, however, were moved from Cuenca but they were the original set at Cuenca where they were replaced by Baroque stalls. The set that was destroyed at Tomar has also not been replaced with Gothic stalls. It should also be noted that while fewer churches are surveyed in this second volume, the percentage of narrative carvings is higher in Spain than in France where many of the early carvings are foliate.

750 misericords with narrative motifs have been identified on the Iberian stalls as compared with over one thousand in France. Such comparisons indicate the richness of the Iberian stalls, which have over twice as many narrative carvings per ensemble as the French stalls. This profusion of carvings necessitates a rather lengthy iconographic index in this volume. Most of the motifs on stalls in north and central Europe are repeated on the Iberian stalls. There are, however, fewer examples of some themes and more of others. It is rare in Iberia to find a carving of a New Testament scene. No set is concerned totally with the Old Testament as at Amiens and the former set at St Victor of Paris. However, Aristotle still carries Phyllis on his back, the fox preaches to the barnyard animals, the mermaid carries her mirror and comb and the peasant carries his sack to ease the burden on the donkey. The proverbs in Spain and Portugal are mainly Flemish with some additional local sayings. We see more of Hercules in Iberia and more illness.

In addition to carved misericords in Iberia, sculptures adorn the arms, dorsal panels, canopies, and partitions between the seats, arm-rests and other structural components. Some of these elements, such as canopies on the base stalls and canopy dividers (roundels or teardrop-shaped projections at the junction of the canopy with the dorsal panel on both base and high stalls) do not even exist on the choir stalls of other countries. Arm-rests in Iberia are usually elaborate and complement the motifs on the misericords. The profane carvings on these parts of the stalls are listed briefly in this volume since they are usually directly related to the misericord motifs. The battling couple may be seen not only on misericords but also on arm-rests, jouée panels, dorsal friezes and interdorsal roundels. The fable of The Fox and the Stork is repeated no less than four times on different parts of the Oviedo choir stalls. The men who carry the riches from the Promised Land on a Toledo misericord, show their fatigue by dropping their burden on a capping rail frieze. A mermaid swims on a misericord but attacking monsters surround her on a dorsal frieze. The repetition of profane carvings is unusual on choir stalls in other countries. At Hoogstraten in Belgium, however, a man gapes before the oven on a misericord and also on an arm-rest.