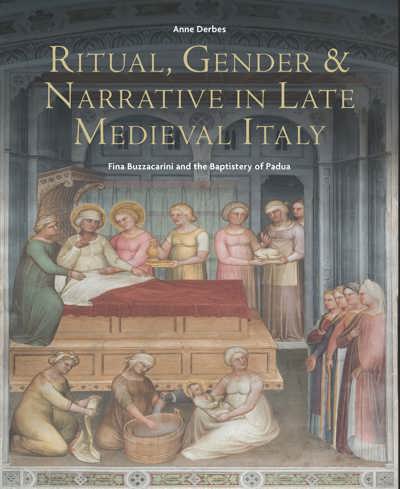

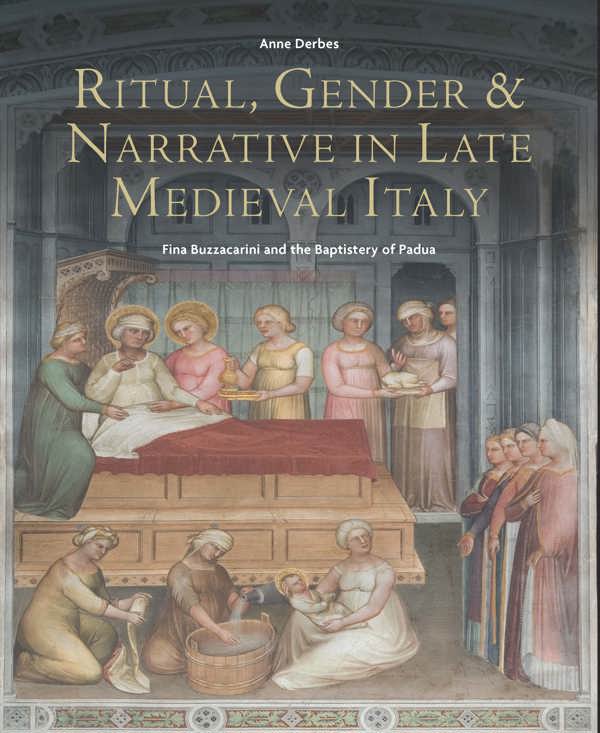

Ritual, Gender, and Narrative in Late Medieval Italy

Fina Buzzacarini and the Baptistery of Padua

Anne Derbes

- Pages: 384 p.

- Size:225 x 280 mm

- Illustrations:188 col.

- Language(s):English

- Publication Year:2020

- € 150,00 EXCL. VAT RETAIL PRICE

- ISBN: 978-2-503-57968-9

- Hardback

- Available

This volume is the first English-language study of the baptistery of Padua and its extraordinarily rich fresco program, commissioned by a woman, Fina Buzzacarini, in the 1370s. She had the sacred space reshaped into a family mausoleum, though it continued to function as the town’s baptistery. This study uses close visual analysis to argue that the frescoes, painted by Giusto de’ Menabuoi, dovetail with the interests of Fina Buzzacarini and at the same time participate in the ritual of baptism; and that ritual and gender are ultimately interlayered in this complex space.

“The publication of Anne Derbes’s lavishly illustrated book on the baptistery of Padua is a welcome and timely contribution, both for this building and the city.” (Louise Bourdua, in CAA Reviews, 4, 2022)

“(…) Derbes provides a rich and compelling contribution to the history of the medieval artistic legacy of Padua. One of this book’s strengths lies in an approach that contextualizes readings of the baptistery’s imagery in terms of both the civic dialogue between the ruling class and its citizens but also the city’s traditions, rituals, and ceremonies. (…) One of the most appealing aspects about this book is that Derbes has provided a highly contextualized account of this monument’s place in history. It will appeal as equally to art historians as it will to historians of medieval society, culture and liturgy, women’s studies, and historical musicologists.” (Jason Stoessel, in Mediaevistik, 34, 2021, p. 481)

“Having proven so convincingly Fina’s association with the generative imagery in the biblical narratives, Derbes lays the ground for understanding that baptism is also implicated in the lineage of Christian Whiteness for which the white robes of the baptized, the Holy Innocents, and the martyrs of the Apocalypse serve as symbolic reminders.” (Thomas E. A. Dale, in SPECULUM, 99/2, 2024, p. 567)

Anne Derbes, professor emerita of art history at Hood College, is the author of Picturing the Passion in Late Medieval Italy: Narrative Painting, Franciscan Ideologies, and the Levant, the co-author of The Usurer’s Heart: Giotto and Enrico Scrovegni in the Arena Chapel, Padua, and co-editor of The Cambridge Companion to Giotto. Her articles have appeared in The Art Bulletin, Gesta, Speculum, The Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, and other scholarly publications.

Ritual, Gender, and Narrative in Late Medieval Italy is the first English-language study of the baptistery of Padua and its extraordinarily rich fresco program, which opens with Genesis and closes with the Apocalypse. Remarkably, when the building was refashioned and frescoed by Giusto de’ Menabuoi in the 1370s, it was a woman, Fina Buzzacarini, who funded the enterprise. In late medieval Italy, baptisteries were potent symbols of civic identity, solidarity, and pride, and towns spent lavishly on them – but no other baptistery was so radically reworked at the behest of a woman. Remarkably, too, though the building continued to function as Padua’s baptismal church, the renovations transformed it into the mausoleum of Fina Buzzacarini and her family. This volume takes an interdisciplinary approach, using close visual analysis to argue that to a surprising degree, Fina exerted control over the images. The author argues too that ritual is equally important in understanding the frescoes: that in multiple ways that have rarely been considered, the images respond to and participate in the ritual enacted in this sacred space. The prayers intoned at the font, the actions of the officiant, the hymns chanted in procession and inside the baptistery, and even details of the rite all find visual echoes on the baptistery’s walls. Ultimately, gender and ritual intersect in the multilayered frescoes of the Padua baptistery.

Introduction

Chapter 1 Fina Buzzacarini in Carrara Padua

Local chroniclers say little about Fina, but recount one salient aspect of her life: after marrying Francesco I Carrara in 1345, she failed for over a decade to produce the requisite son and heir. After crises at court over succession, in 1359 she gave birth to a son. Though the couple’s marriage was strained by her husband’s blatant philandering, previously overlooked records show that Fina, a very wealthy woman, gradually emerged as a powerful presence at court. While some have minimized the degree of Fina’s responsibility for the baptistery’s program, I cite a number of documents from the later trecento that attest to a woman’s ability to shape the subject matter of a work that she funded. I next discuss Fina’s tomb monument, which emulates those of earlier Carrara lords but outshines them, and her votive portrait, which places her on the dexter side, as sole donor, and excludes her husband. Finally, I consider the extraordinary small portraits of Fina inserted into several of the narratives and interpret them as assertions of her authority, overt claims of agency, injected through the program.

Chapter 2 Baptistery as Mausoleum: Ambitions and Motivations

Why would Fina have sought the baptistery as a burial site, and why did Francesco and the local bishop, whose approval would have been required, agree? The sacred space of a baptistery had long been understood as a desirable funerary site. For Francesco, the project meant the embellishment of one of the most important buildings in the city, burnishing the stature of the regime; co-opting the preeminent symbol of civic harmony; and creating a prestigious–and presumably spiritually advantageous—setting for his own tomb. For the bishop, given the brief tenures of his predecessors who dared to cross Francesco, attempting to thwart the project was not a viable option. Fina likely had reasons of her own, which I consider further in Chapter 6, for choosing the baptistery as her burial place. Here I note that baptisteries were uncommonly welcoming to women. The rite offered them a rare opportunity to participate in the liturgy: women took their place at the font next to men. Finally, in electing her burial in the baptistery, Fina insured that her tomb would be seen, and her memory preserved, by future generations.

Chapter 3 Narrative, Ritual, Exegesis: The Genesis Cycle

This chapter opens with an account of the baptismal ritual as performed in late medieval Italy– the choreography of prayers, chants, readings, ritual actions, and attendant customs for both the solemn rite and the individual rite. The rest of chapter 3, and chapters 4 and 5, analyze the frescoes in the narrative cycles, arguing that they are as carefully choreographed as the rite, and work in concert with it. They respond as well to baptismal theology, depicting themes that offer pictorial glosses on the rite, echoing typological parallels drawn by medieval exegetes. The Genesis cycle in the drum of the dome includes narratives both familiar and more obscure (the Death of Adam; Lamech Slaying Cain; Jacob’s Prayer after his Dream; Jacob’s Rods; the Reunion of Jacob and Esau). The obscure episodes are distinctly baptismal, and even the familiar ones are rendered in unusual ways that heighten their baptismal resonance.

Chapter 4: Narrative, Ritual, Exegesis: The New Testament Cycle

The baptismal themes introduced in the drum continue below, in the New Testament cycle, where the frescoes are often strategically sited to respond to others, each accruing meaning from those nearby. Because of these pictorial and thematic correspondences, it is most productive to analyze the frescoes spatially, wall by wall, rather than purely chronologically. While most of the New Testament episodes depicted here are commonly seen in trecento visual narrative, almost all have been adapted in ways that make them singularly appropriate to the site. For instance, in the Massacre of the Innocents, the slain babies, normally shown nude in trecento painting, wear white tunics that evoke the white garments given to infants after baptism; the jugs in the Marriage of Cana are enlarged versions of the ewer used in the baptismal rite.

Chapter 5: Narrative, Ritual, Exegesis: The Apocalypse Cycle

In the baptistery’s apse is a remarkably detailed depiction of the book of Revelation, a subject seldom seen in trecento painting and never on this scale. The choice was well considered: from late antiquity into late medieval Italy, exegetes found in the text repeated allusions to the sacrament. Again, uncommon narrative inclusions, such as the opening of the fifth seal, with the giving of white garments to the souls under the altar, or idiosyncratic features, like the setting of scenes in dramatic seascapes that attest to the salvific potency of water, highlight the relationship between the images and the rite enacted here.

Chapter 6: Gender Matters: Maternity, Sexuality, and Visual Rhetoric

If the Padua baptistery is a site for the celebration of the liturgy, it is also a site for the celebration, and commemoration, of its patron. Chapter 6 returns to the visual evidence to examine Fina’s role in the baptistery more closely. The gender symmetry of the dome, where women and men appear in equal numbers in the largest circle of Paradise, is suggestive. So is the Genesis cycle’s insertion of women into the narrative, at times almost rewriting sacred history to insist on their active participation at critical junctures. Moreover, many of the women featured in the dome and the drum are, unlike most women in the Christian pantheon, mothers – significantly, mothers of sons. Several (Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, Elizabeth) conceived and delivered sons only after a long delay. Important, too, is the Apocalyptic Woman of Rev. 12, prominently depicted in the apse, who gave birth to a son born to rule. All of these women serve as Fina’s exemplars – and as reminders of her success in delivering her own long-awaited son. Finally, the frescoes also feature malevolent, and specifically sexually transgressive, women: Herodias, the wife of Lot, and the Whore of Babylon; all are visually juxtaposed with virtuous mothers, and Herodias, who had an adulterous relationship with a ruler, with Fina herself.