Portraits of the City

Representing Urban Space in Later Medieval and Early Modern Europe

Katrien Lichtert, Jan Dumolyn, Maximiliaan Martens (eds)

- Pages: vi + 212 p.

- Size:178 x 254 mm

- Illustrations:80 b/w, 14 col.

- Language(s):English, French

- Publication Year:2014

- € 95,00 EXCL. VAT RETAIL PRICE

- ISBN: 978-2-503-55226-2

- Paperback

- Available

- € 95,00 EXCL. VAT RETAIL PRICE

- ISBN: 978-2-503-55259-0

- E-book

- Available

"Autant d'études qui chacune à sa façon apportent du nouveau sur les modalités de la représentation urbaine dans la première modernité." (dans: Bulletin de la Société Française d'Étude du Seizième Siècle, n° 80, décembre 2014, p. 47)

“(…) this is a useful collection that draws attention to an interesting range of examples (…)” (Fabrizio Nevola, in Renaissance Quarterly, 69/4, 2016, p. 1449)

Maximiliaan P. J. Martens is professor in Fine Arts and chair of the Department of Art, Music and Theatre Sciences, Ghent University.

Jan Dumolyn is a senior lecturer at Ghent University, Department of History.

Katrien Lichtert has recently finished her PhD on Pieter Bruegel the Elder and the representation of urban landscapes at Ghent University.

During the last decades, representations of medieval and early modern urban space have witnessed an increasing popularity as objects of study within the historical disciplines. Scholars with different backgrounds investigate urban landscapes in various forms and using a wide range of media. In general, such ‘portraits of the city’ cover different types of visual and written documents. The twelve essays gathered in this book all cover specific types of such portraits, ranging from historiographical texts and archival record, over drawings, prints and paintings to maps and real urban architectural settings. Moreover, the interdisciplinary scope results in an ample compilation of various innovative methodologies, currently applied in the fields of study and disciplines addressed in the book. ‘Portraits of the City’ provides a representative overview of the current state of knowledge and is in this way a relevant contribution to the international debate on representations of the city.

In the first paper, Vannieuwenhuyze and Vernackt focus on the use of historical town views and maps by urban historians. They introduce and illustrate a methodological tool called ‘Digital Thematic Deconstruction’ which allows exploiting historical town views and maps more profoundly, to discover ‘hidden’ features and patterns, and to discuss their accuracy and meaning(s). One of the advantages of the ‘Digital Thematic Deconstruction’ is that it enables the researcher to study the urban topography more accurately. Also, the method appears to be useful to unravel certain symbolic messages underlying the representation of the town.

In the second paper, Petra Maclot uses the birds’-eye view of Antwerp by Virgilius Bononiensis (1565) as a source for typological research of private buildings in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Antwerp. Maclot demonstrates that the physical landscape of medieval cities, whether still visible in the town plan or in the remaining architecture, also entangles a strong representational dimension, functioning as a marker of past experiences and ideologies. Also, architecture served the construction and promotion of identities of individuals or particular social groups. Specific styles or building typologies often reveal a particular significance regarding social status, as is illustrated by Maclot’s analysis of the private urban buildings depicted in Bononiensis’ map.

The third contribution, by Chodejovska and Krejcí, provides a technically elaborated case study, analyzing two plans of Prague by Joseph Daniel Huber dating from the second half of the 18th century. From a methodological point of view, the authors employ a set of cartometric analyses including the use of georeferencing. Using such specific analytical tools, they succeed in visualizing Huber’s plans, making them accessible to a large audience for the first time.

In his paper on Early Netherlandish panel painting, Jelle De Rock submits a vast corpus of pictorial cityscapes to a quantitative analysis. The author determines several shifts or modes in the various representations of the city from c. 1420 to 1520. For example, from the mid-fifteenth century onwards, profile views became increasingly popular and the number of ‘interior views’ decreased in favour of representations focussing on the monumental architectural features of the city.

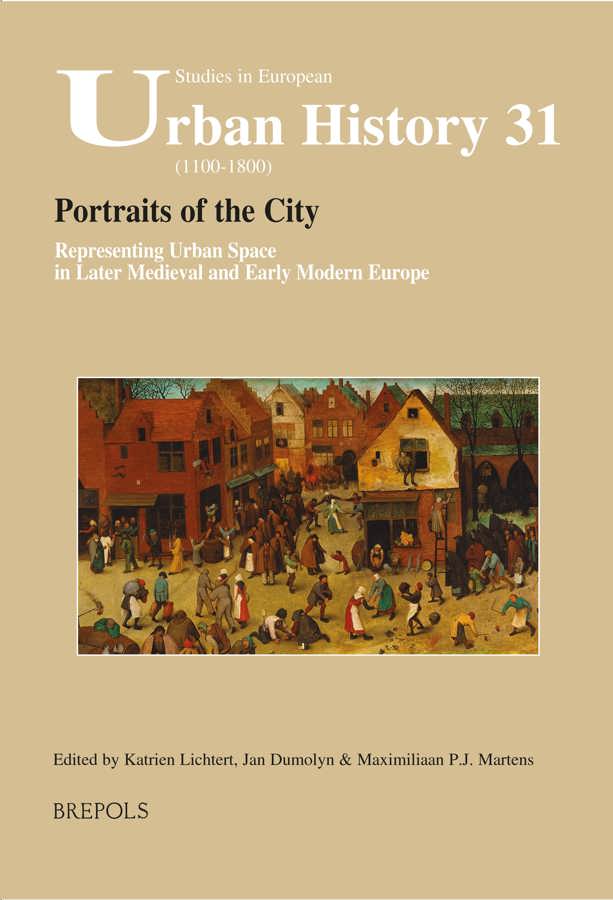

Katrien Lichtert’s paper is based on an in-depth analysis of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s ‘Battle between Shrovetide and Lent’ (1559). This oil painting is one of Bruegel’s so-called ‘encyclopeadic’ works and the cityscape in which Bruegel locates the scene is analysed in relation to contemporary social and cultural practices. The author succeeds in revealing information on Bruegel’s use of different representational modes and more specific on the relation between the artist and particular local cultural practices such as urban theatre and other practices related to the local rhetoricians or ‘rederijkers’.

In his essay, Oliver Kik investigates the so-called ‘antique style’, an architectural idiom emerging in the Netherlands in the first half of the 16th century and permeating different media. This ornamental style was inspired by the Italian Renaissance and favoured by the Burgundian-Habsburg court and high nobility. Moreover, as is illustrated in Kik’s essay, this antique idiom strongly infuenced the depiction of architectural urban landscapes in the Netherlands. In particular, the author focuses on Bramantesque and Lombard sources in defining the character of this architectural language in Netherlandish painting in the first decades of the sixteenth century.

Cecilia Paredes analyses some magnificent examples of city portraits in tapestries from the Habsburg imperial collection. More specific, Paredes focuses on representations of Brussels, Constantinople, Pavia, Barcelona and Tunis; the latter two forming part of the series of the Conquest of Tunis (1549-54), a twelve-piece set designed by Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen, commemorating the Emperor’s heroic crusade of 1535. The author demonstrates that such city portraits clearly functioned as powerful and ideological tools.

The next contribution is by Maria Clelia Galassi, who investigates two 16th-century portraits of Genoa, one by the famous painter and engraver Anton van den Wijngaerde and the other by Jan Massys. Furthermore, the author describes the ‘celebration’ of Genoa in terms of idealistic and mythological transfiguration, as in a literary laudatio urbis.

In her paper 'Describing and ‘Mapping the Town’ using Iconographic and Literary Sources. Cities in the Late Middle Ages in Italy', the architectural historian Silvia Beltramo examines the different social and architectural elements that constitute the urban space. She does so by using a variety of sources, relying in particular on iconographic and historical documents (legal documents, tax records, registers and statutory decrees), as well as physical witnesses (architecture and archaeology) and literary records including contemporary chronicles or short stories, such as the writings of Boccaccio and Sacchetti. Beltramo’s article shows the advantage of combining literary, documentary and material sources to reconstruct perceived and lived urban space.

Nirit Ben-Aryeh Debby focuses on a particular case study, a vast seventeenth-century panorama of Constantinople designed by the Venetian Franciscan friar Niccolò Guidalotto da Mondavio. Guidalotto also prepared a long manuscript which details the panorama’s meaning and the motivation behind its creation. The author analyses the panorama in a comparative perspective, revealing Guidalotto’s personal agenda and unfolding the city view as a representation of contested space between East and West.

The next contribution by Sarah Van Ooteghem concentrates on 16th-century vedute, drawn by Netherlandish artists travelling to Italy. Van Ooteghem examines the methodological aspects of 16th-century Roman vedute as historical sources and doing so, she simultaneously sheds light on the concept of ‘drawing from life’ (‘naer het leven’) in 16th-century artistic practice.

The last paper by Megan Williams focuses on early modern diplomatic portraits of Rome. These textual portraits depict the ways in which different diplomats experienced and navigated the city and apparently, Rome was often metaphorically depicted as a theatrum or public stage. On the textual level, the diplomats studied by Williams ‘portray’, as it were, the civil qualities of Rome according to the contemporary stylistic norms of letter-writing.