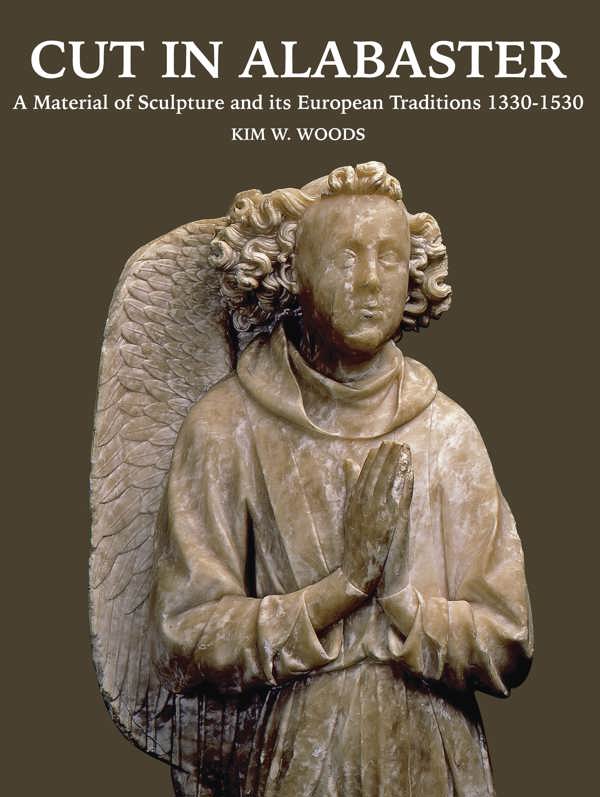

Cut in Alabaster: a Material of Sculpture and its European Traditions 1330-1530

Kim Woods

- Pages: 422 p.

- Size:220 x 280 mm

- Illustrations:5 b/w, 194 col.

- Language(s):English

- Publication Year:2018

- € 150,00 EXCL. VAT RETAIL PRICE

- ISBN: 978-1-909400-26-9

- Hardback

- Out of Print

Cut in Alabaster is the first comprehensive study of alabaster sculpture in Western Europe during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance.

“Woods has given us a rich analysis of an important medium and many prestigious works that adopt it. She has traced its production and marketing across a great geographical expanse with sensitivity and skill, offering insights about a number of celebrated monuments. This book should command a wide audience interested in late medieval and early modern art and culture.” (Ethan Matt Kavaler, in Historians of Netherlandish Art Reviews, May 2019)

“The book is also a pleasure to use, whether dipping in for a specific reference or reading from cover to cover, with beautiful photographs (many taken by Woods) and a crisp, unfussy layout. We have had to wait a long time for such an intelligent and well-researched overview of European late medieval alabaster sculpture, but have been rewarded with a splendid and multi-faceted volume that will both stimulate the student and inform the specialist.” (Paul Williamson, in The Art Newspaper, 314, 2019, p. 11)

“Insgesamt (…) ist Cut in Alabaster ein sehr wichtiges und wertvolles Buch, das Grundlagen für die weitere transnationale Erforschung der Alabasterkunst schafft und auch als ein Vorbild für vertiefte Studien zu anderen Materialien dienen kann.” (Aleksandra Lipińska, in Sehepunkte 20 (2020), Nr. 5 [15.05.2020])

Kim Woods is a senior lecturer in Art History at the Open University, and a specialist in northern European late Gothic sculpture. She combines an object-based approach with an interest in materials and cultural exchange. Her single-authored book, Imported Images (Donington, 2007), focussed on wood sculpture. Since then she has been working on alabaster. Her Open University distance learning materials include the Renaissance Art Reconsidered volumes (Yale, 2007) and Medieval to Renaissance (Tate publishing, 2012).

While marble is associated with Renaissance Italy, alabaster was the material commonly used elsewhere in Europe and has its own properties, traditions and meanings. It enjoyed particular popularity as a sculptural material during the two centuries 1330-1530, when alabaster sculpture was produced both for indigenous consumption and for export. Focussing especially on England, the Burgundian Netherlands and Spain, three territories closely linked through trade routes, diplomacy and cultural exchange, this book explores and compares the material practice and visual culture of alabaster sculpture in late medieval Europe. Cut in Alabaster charts sculpture from quarry to contexts of use, exploring practitioners, markets and functions as well as issues of consumption, display and material meanings. It provides detailed examination of tombs, altarpieces and both elite and popular sculpture, ranging from high status bespoke commissions to small, low-cost carvings produced commercially for a more popular clientele.

Chapter 1 is entitled Alabaster as a material of sculpture and explores the properties of the material that forms the focus of the book. It looks at the similarities and differences between alabaster and marble, their use and status in the period 1330-1530, considering their relative cost and advantages and disadvantages. The distribution of alabaster quarries and practical issues surrounding quarrying are also discussed together with tools, techniques and typical polychromy schemes.

Chapter 2 is entitled Makers, Markets and Methods, and introduces a range of European alabaster sculptors including elite court sculptors and more commercially-oriented alabaster specialists. The distribution of imported works in alabaster in the Baltic, the Iberian peninsular and Italy is used to show that the demand for alabaster sculpture was not restricted to the domestic market. The extent to which carving methods were adapted to meet the demands of rapid production and long-distance trade is also considered.

Chapter 3 is entitled Case studies in makers and markets: The Master of Rimini and Gil de Siloe, which compares and contrasts the two very different models of alabaster sculpture introduced in chapter 2. The so-called Master of Rimini was an alabaster specialist who participated in a luxury export trade in alabaster sculpture while Gil de Siloe received a one-off elite commission for the Castilian royal tombs at Miraflores.

Chapter 4 is entitled The status and significance of alabaster. Here a range of possible material meanings are considered in relation to court culture, religious practice and identity, whether social, gender or national. The status of alabaster in comparison with bone, ivory and the early Netherlandish painting of Jan van Eyck is also discussed.

Chapter 5 is entitled Three projects in alabaster, and explores the material meanings introduced in chapter 4 in three different contexts. The first is the tomb of Edward II at Gloucester, the earliest known to have been made in alabaster in England, and the identification of alabaster with the court of Edward III. The second project is the alabaster tomb of Charles the Noble of Navarre and his selection of alabaster as an equivalent to the marble tombs distinctive of the French monarchy. The third is Margaret of Austria's adoption of alabaster at her foundation at Brou, self-consciously drawing on Burgundian material traditions.

Chapter 6 considers the genre of alabaster tombs The period 1330-1530 marks the heyday of the European alabaster tomb, and alabaster was clearly an elite material associated with royal, noble or ecclesiastical status. The themes of continuity and convention, identity and allegiance, and imitation or rivalry are explored. All played a part in the trickle down adoption of alabaster from the ruling elite to an ever-widening range of social classes in this era of the alabaster tomb.

While Chapter 6 focused on tomb types, Chapter 7 presents three case studies of bespoke tombs, where patrons demanded unexpected and unusual designs. The first, the tomb of René of Anjou, is known only through documents. The second, the semi-recumbent 'Doncel' in Siguenza Cathedral, has entered popular imagination for its originality but relates nevertheless to a group of bespoke Iberian tombs. The third, the tomb of Engelbrecht of Nassau, brings the bespoke alabaster tomb into the Renaissance.

Chapter 8 explores the second genre particularly associated with alabaster: altarpieces. The evolution of differing conventions of alabaster altarpieces in north-western Europe and the Iberian peninsula are charted, compared and contrasted. Although the designs used in either wood or stone altarpieces were sometimes translated fairly literally into alabaster, alabaster was also used for bespoke works of art where both design and iconography were purpose-made.

The final chapter, chapter 9 is entitled Genres of alabaster in public and in private. Paradoxically, alabaster could serve both a luxury and a popular market, and this chapter considers both. At one extreme there are repetitive, popularising works produced according to relatively fixed conventions such as St John's heads. At the other extreme are a series of luxury alabasters displaying all the hallmarks of high status commissions: bespoke designs with unexpected and thoughtful iconography and lavishly-detailed facture. Many are also relatively small and suitable for private scrutiny, but alabaster monumental alabaster statues and grand narratives suitable for public places are also discussed.